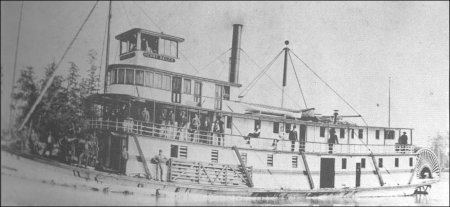

| Until railroads arrived in Skagit county in 1889, sternwheeler steamboats like the Henry Bailey, pictured here, were the lifeline for both transportation and freight, in addition to shipping mineral ore. This boat was owned at one time by centenarian banker Joshua Green, who said that it could "float on a puddle of dew" because of its shallow draft of less than two feet. That allowed these sternwheelers to navigate the shallow sloughs of the Skagit delta, land their bow on the slope of a farm, load up and shove off backwards. Photo courtesy of the fine book, Chechacos All, which is reprinted and available for sale at the Skagit County Historical Society Museum in LaConner.

|

We who research the history of Skagit county and the Pacific Northwest are most fortunate to have the 1906 Illustrated History book, as a source book. It was published by the Interstate Company of Chicago, which produced similar books for counties all over the country. The back half included biographies which were paid for by pioneer families, which underwrote the costs of production. The front half, however, was written by journalists who were familiar with the area and went into the field to interview living pioneers and research the surviving copies of frontier newspapers. In this case, one of the writers was the young Harry Averill, who wrote for local papers and, after a stint in California, came home to edit the Mount Vernon Herald. We have surveyed subscribers to determine what they most want to read and many requested transcripts from this book, which is very rare and difficult to access outside of libraries and collections.

|

810 Central Ave.,

810 Central Ave.,