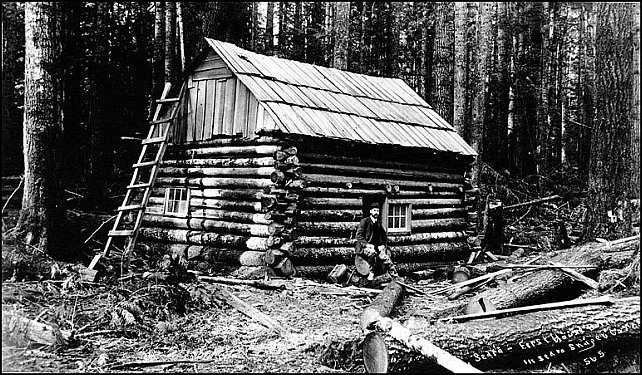

Years ago, the late Howard Miller showed me this copy below of what was one of the earliest photos of the future-Sedro area. It was taken by Arthur Churchill Warner in 1894 and he wrote on the photo: "First house built in Sedro, Skaget Co., Wash." By good fortune, the University of Washington Special Collections has the original (number WAR0593). Unfortunately we have not been discovered where the cabin was or who it belonged to. It could have belonged to any of the four British bachelors who homesteaded the future acreage or Sedro — Batey, Dunlop, Hart and Woods. Or it could have been David Batey's first cabin that he built near the Skagit River before he built his 2-story house a mile north on the bench. Or it could have been the cabin built by Lafayette Stevens at future Sterling, circa mid-1870s, or it could have been the one that Jesse Beriah Ball built near his mill at Sterling. Just like with the derivation of the name, Sterling, we may never know.

We researched Warner and discovered that he had a photo studio, Warner & Randolph, at Room 71, the Hinckley Building, at the corner of 2nd and Columbia streets, Seattle. Like many others, he came out to Washington Territory with the Northern Pacific Railroad, in 1886. Two years later, 1888, naturalist John Muir hired Warner to join and photograph a Mt. Rainier climbing expedition party. See more background on the photo and the photographer at our Story #1 on the site, From Bug to the Bughouse. We continue researching to find where the house was located but so far we suspect that it was built before Cook arrived at his river location.

|

Covering from British Columbia to Puget Sound. Washington counties covered: Skagit, Whatcom, Island, San Juan, Snohomish, focusing on Sedro-Woolley and Skagit Valley.

Covering from British Columbia to Puget Sound. Washington counties covered: Skagit, Whatcom, Island, San Juan, Snohomish, focusing on Sedro-Woolley and Skagit Valley. This page originated in our Optional Subscribers Magazine

This page originated in our Optional Subscribers Magazine  An evolving history dedicated to committing random acts of historical kindness

An evolving history dedicated to committing random acts of historical kindness  The home pages remain free of any charge. We need donations or subscriptions to continue.

The home pages remain free of any charge. We need donations or subscriptions to continue.  Please pass on this website link to your family, relatives, friends and clients.

Please pass on this website link to your family, relatives, friends and clients.