Site founded Sept. 1, 2000. We passed 4.5 million page views on Nov. 29, 2010

The home pages remain free of any charge. We need donations or subscriptions to continue.

Please pass on this website link to your family, relatives, friends and clients.

|

|

of History & Folklore

Subscribers Edition, where 450 of 700 stories originate

The most in-depth, comprehensive site about the Skagit

Covers from British Columbia to Puget Sound. Counties covered: Skagit, Whatcom, Island, San Juan, Snohomish & BC. An evolving history dedicated to committing random acts of historical kindness

|

Lafayette Stevens, Skagit coal mining genius

and early upriver Skagit settler from 1873

By Noel V. Bourasaw, publisher of the Skagit River Journal of History & Folklore

|

Lafayette Stevens, photo found by historian Deanna Ramey Ammons in a scrapbook in a thrift store

|

Lafayette Stevens had the look of a riverboat gambler. When he arrived at LaConner in Washington territory sometime by 1873, he was the most experienced miner on the Skagit river and from then until the early 1900s he had his finger in almost every pie, especially those having to do with coal. His role in the future Cokedale mines alone made him the point man for the seminal event that led to the birth of Sedro and Woolley.

For such an active man, who was present at so many important times in the early days of settlement, Stevens left very little public record. Luckily a small reference to him on the website caught the eye of one of his shirttail relatives, and contacts with the family have helped us form a picture of the man. The first mention of him is in the Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties, published in 1906 [hereafter called the 1906 Book]. A subchapter on the early coal prospecting in the area notes that Amasa Everett and Orlando Graham arrived in 1873 and met Stevens while they all worked on the Swinomish flats the next spring. The 1906 Book notes only that he "came to the Skagit country about that time." While boarding at LaConner, the men met some Indians who had come downriver to trade and showed samples of a strange yellow metal. All the references that have been made to that event imply that the Indians were ignorant of the properties of gold and their value. We find that questionable. Regardless, in late September that year the three adventurers paddled up to the long log jams at Mount Vernon, portaged around them — probably with Indian guides, and poled up to the future site of Hamilton. Stevens and Everett were intent on finding more of the placer gold, but Graham, who had no mining experience, paid attention to the report of Indians who lived there that they had found a peculiar black metal in the mountains across the river. Graham was a natural leader, having been a first lieutenant under William Tecumseh Sherman in the famous 1865 march to the sea across Georgia, and the other two men followed his suggestion.

Any time, any amount, please help build our travel and research fund for what promises to be a very busy 2011, traveling to mine resources from California to Washington and maybe beyond. Depth of research determined by the level of aid from readers. Because of our recent illness, our research fund is completely bare. See many examples of how you can aid our project and help us continue for another ten years. And subscriptions to our optional Subscribers Online Magazine (launched 2000) by donation too. Thank you.

|

They all crossed the river and ascended Coal Mountain, where they indeed found much coal. On one of the first trips up the mountain, Everett was caught unaware when a bolder rolled down a slope and his leg was crushed. Graham rushed him downriver and surgeons in Seattle tried to save the leg, but to no avail. Tough and determined, Everett fashioned a prosthesis during his recuperation and headed back for the river, known from them on as "Pegleg." Regardless of the timing, the partners set about organizing a mining company and finding investors who would grubstake the three partners and provide capital to hire labor and equipment to sink a shaft down into the mountain. James J. Conner, who owned the LaConner House hotel where the original partners originally boarded, and the investor who grub-staked their original trip, became a principal as did James O'Loughlin, a LaConner tinsmith who would also become a hotelier. Conner was cousin to John S. Conner, founder of the town, and James suggested that his cousin use his wife's initials, L.A., to coin the name of the village. According to JoAnn Roe's book, Ghost Camps and Boom Towns, the partners incorporated on Sept. 18, 1875, as the Skagit Coal Co. for $960,000. Offices were established in LaConner and Stevens and his original partners were named as trustees, along with six other trustees, including Henry L. Yesler, who opened the first sawmill in Seattle in 1853. Conner recalled in 1906 that he originally dispatched the three adventurers on their trip upriver and said that he had first learned of the coal from an Indian chief. Everett also said in his own paid biography that Conner grubstaked the men.

Now capitalized, the company filed upon 160 acres of coal land on the north face of the mountain and in 1875 the partners hired laborers to sink a shaft 100 feet deep. That first year, they shipped 20 tons of coal ore to San Francisco, which was growing rapidly and needed coal for heat and steam boilers. One must remember that there was no rail transportation for the ore, so it could only be shipped downriver by canoe. Working with Indians, the company took two large cedar canoes and strapped a jerry-built container on top and headed downriver. The log jams were 25 miles away and there was no way to hack a trail through the trees growing out of the jam, and the thick underbrush and twisted logs, so the men hacked a trail two miles around the jams to the west on the river shore, along the route they used the year before to transported the injured Everett. Once the trail was finished, they hired teams of Indians and a handful of local settlers to pack the ore on sleds to the southernmost end of the lower jam and they contracted the steamer Chehalis to carry the ore the rest of the way to bunkers in Seattle. The partners soon learned, however, that the added costs of shipping the ore that way cut considerably into the company's profits, so shipments slowed to a trickle. The mine subsequently remained undeveloped for two years until Conner gained other resources, promoted it again for a number of years, and ultimately sold or bonded the company to the Skagit-Cumberland Coal Co., a group of San Francisco and Seattle investors. Roe found a record that Everett sold his share of the claim to O'Loughlin and Conner in October 1875, and Stevens and Graham may have sold out, too, because we find no more record of their involvement. The 1906 Book notes that Stevens staked a claim at the site of future Sterling about the same time and subsequently lived there for the next ten years or so.

Native of Illinois

Stevens was born Aug. 22, 1847 in Burton Township, McHenry County, Illinois, the son of Alfred and Esther (Kellogg) Stevens, natives of Pennsylvania. Alfred's maternal grandfather, Asher Merrill, fought at Bunker Hill and other Revolutionary War battles; his paternal great grandfather also fought in that war. Lafayette's parents moved from Wayne County, Pennsylvania in 1837, to English Prairie, also in McHenry County, near present day Spring Grove, Illinois, and eventually raised nine children on their farm. Alfred appears to have been successful at amassing property. His holdings started as a quarter section of 160 acres and he added on land until it totaled 700 acres of what became prime land near the Wisconsin border, in addition to a large block of land near Clear Lake, Iowa, according to Dan Stevens, who is Lafayette's first cousin, twice removed. Joy Lester, Lafayette's great niece, learned that Lafayette — ever the promoter, exaggerated in his paid biography for the 1906 Book. He claimed that his parents once owned 320 acres where Chicago later stood, but there is no foundation for that. In the same biography, he recalled that he stayed at home to help farm and complete school nearby until he was 19, and then farmed elsewhere in Illinois until he moved at age 23 to California in 1870. According to differing accounts, he either worked on a ranch near Chico for about a year or he taught school — maybe both, and then moved to Nevada in 1871, where he began prospecting, his main career for the rest of his life. In the two and a half years he spent there, he found several good paying claims and was successful, according to the 1906 Book.

We have not yet read why Lafayette Stevens moved to the Skagit river in 1873. Something special must have attracted him if we are to believe his story about his success in Nevada. Argonauts did move about the west for hundreds of miles, literally overnight, but they were usually stimulated by a strike of some kind. The Fraser river gold rush to the north in 1858 was pretty short in duration and a few years later there was a strike a hundred miles north of there in the Cariboo, but miners seem to have been discouraged about prospects here. The log jams at future Mount Vernon were a real impediment on the Skagit river until the late 1870s so we wonder what could have brought him here in 1873.

Stevens and the Cokedale mines

|

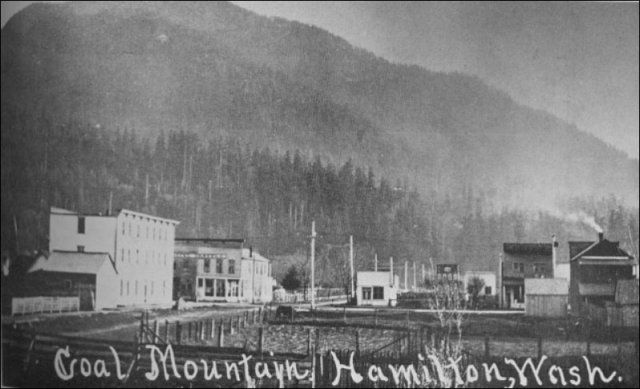

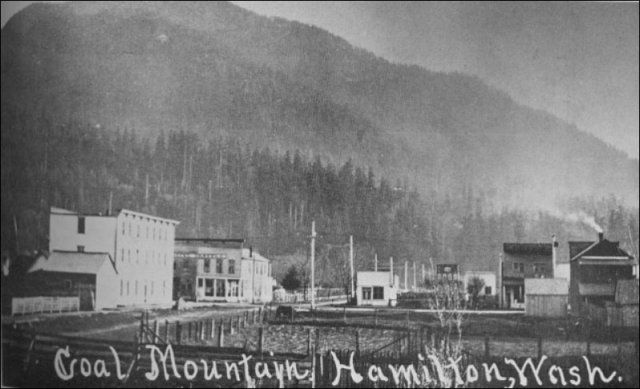

This undated photograph was often printed on postcards near the turn of the 20th century. The view is looking south over the young town of Hamilton, with Coal mountain looming behind on the south shore of the Skagit river. We hope a reader can identify when it was taken and what the buildings are in the photo.

|

The next record we have for him after the Hamilton coal venture is that he found a coal seam four miles northeast of future Woolley, at a site that eventually became known as Cokedale. Roe found a report in the archives of the Northwest Mining Journal that the Skagit coal fields were newer than the carboniferous age [about 280 million years ago] but older than the Cascade mountain range: "Geologists speculated that the Cokedale deposits were the same as that of Hamilton, and later geologists believed that the Hamilton, Cokedale, Blue Canyon, and large Bellingham coal deposits were all part of the same veins that extended northwesterly under the Georgia Strait to Nanaimo on Vancouver Island." Without rail transportation, however, the site presented more transportation problems since the mining claim was about six miles from the river and the forest was so thick on the route that even an average wagon ride took two hours. Besides, one of the logjams was still present downriver. Stevens would have to wait for a railroad, so he pursued other interests for the time being.

Later in 1878, Stevens joined his Sterling-area neighbor, Otto Klement, and settlers Charles von Pressentin and John Rowley, who climbed the rugged foothills of the Cascades a hundred miles from the mouth of the Skagit and found placer gold at Ruby and Granite creeks and other locations. Along the way they named mountains, rivers and tributaries to the Skagit, and followed an ancient Indian trail across the Pacific Crest to Chelan county. Their finds caused great excitement as they netted an average of 25 cents a pan, and by 1880, nearly 5,000 miners navigated the river however possible to emulate the miners' success. Roe notes in another of her books, North Cascades Highway, that Stevens was one of the few miners who sustained interest in the area after the Ruby boom went bust. As Jack Durand worked the Colonial Mine on Colonial creek, a tributary of Thunder creek, Stevens joined miners John Rouse, George Rowse and F. Reese who in 1885 found a quartz ledge purportedly rich in gold and silver on the Cascade river. "Such companies mined the land, not the river (placer mining)," Roe notes. "They were forerunners of a substantial boom in the late 1880s and 1890s." True believers continued probing the hills and streams for the next 50 years, cheered on by trained mining specialists like Albert G. Mosier, engineer for both the new county of Skagit after its formation in 1883 and for Sedro-Woolley.

The handwritten diary of a settler about that period includes an intriguing story that may be partially about Lafayette Stevens. Mrs. Eliza Van Fleet, who homesteaded with her husband near the Skagit, wrote about three "men by the name of Taylor, Pamoly and Stevens [who] proved up on claims where a large part of Sedro-Woolley now is and sold their claims to Scott Jameson," presumably in 1878 or thereabouts. We tend to believe that this was Lafayette because Winfield Scott Jameson bought several claims in the Sterling area around 1878 from "paper homesteaders", nomads who squatted on claims and then sold them to cash bidders. Other than those notes, we have found no other record of Stevens until one dated March 8, 1887, when a reporter for the Skagit News in Mount Vernon wrote:

Two hours from Sedro we come to what is the Stevens coal mine and cabin. From the top of the hill we look down 75 or 100 feet to the cabin and entrance where we found George Pierce, the man in charge. He says the coal is equal to the Cumberland coal [in the Appalachians.

According to the 1906 Book, sometime during that intervening nine years Stevens took on two partners in the Cokedale mine. Jesse B. Ball, the founder of future-Sterling, built a logging camp there in 1878 and for the first few years the little village and steamboat stop on the Skagit was called Ball's Landing. Ball and B.A. Marshall became partners with Stevens. Until they had transportation for their coal, they used their limited capital to acquire property from other "paper homesteaders." The only improvement they made at the mine was to dig out one tunnel, 300 feet in length.

Stevens eventually became impatient while waiting for a railroad and the partners sold out in 1888 to Nelson Bennett, who had gained fame with his brother the year before for blasting a tunnel through the Cascades for the Northern Pacific Railroad. Bennett had visions of establishing a terminus at Fairhaven, 25 miles to the northwest, for the transcontinental railroad that entrepreneur James J. Hill was building west over the Rockies — eventually known as the Great Northern. Bennett built the Fairhaven & Southern line, the first standard-gauge, common-carrier rail line north of Seattle, connecting Fairhaven and Mortimer Cook's original village of Sedro on the Skagit on Christmas Eve, 1889. Crews soon built a "wye" with an eastern branch that extended up the hill to Bennett's mine, known as the Skagit Coal & Transportation Co. He did not get his terminus but Hill quietly bought up the F&S line in 1890 and in 1891, C.X. Larrabee, one of Bennett's financial partners, bought the mine. By 1894, coal was shipped by rail to Fairhaven and to connecting trains both north and south. In the meantime Hill bought a quarter interest in the mine and in 1899 he bought the entire property.

One wonders if Stevens realized that he sold out too soon. Frank Wilkeson, a railroad boomer who lived at various times of the year in Sedro, Hamilton and Fairhaven, was a West Coast columnist for the New York Times. In December 1892 he wrote:

When the great Northern Railroad, which is now being extended westward from the Milk River country in Montana to Puget Sound, bought the Nelson Bennett Railroads, that extend from Sedro on the Skagit River to New-Westminster in British Columbia, Mr. James Hill bought this great coal property, and with its output now proposes to control the coal trade of the Pacific coast. He owns the best coal property that I have seen on this coast, and if it is skillfully and economically managed, he will probably be able to set the price of the coal consumed throughout the country west of the Cascade Mountains and in California. This, provided the Skagit-Cumberland group of coal mines [at Hamilton] do not prove to be as valuable as they now promise to be.

Stevens also missed out on becoming an honored town father. Streets in the newly platted town of Sedro were named for both Ball and Marshall in 1889.

Wedding bells for Lafayette

At age 41, Stevens had other matters on his mind in 1888. After he sold the mine property to Bennett, he decided to become a farmer. He was also ready to settle down a bit as well as settle a patch a land. After so many years as a bachelor, a white settler's daughter attracted his eye. Young Florence Drown, born in Wisconsin on Jan. 17, 1872, married Stevens, 25 years her senior, on Dec. 2, 1888. In one of those quirks of history, we find a doubtful statistic. All accounts have them marrying in the town of Burlington, west of Sterling and Sedro on the Skagit, but that date was three years before the town was formed.

The couple lived on 320 acres situated between Sterling and future-Burlington, and farmer Stevens set about clearing 20 acres around their home. The next spring, he followed the lead of west-county farmers such as A.G. Tillinghast and signed a contract to produce garden seed for handsome price of one dollar per pound. Unfortunately, after fifteen years of quiet springs, the Skagit river went on a rampage in June 1889 and what was called a spring "freshet" or flood washed away his entire planting. Sterling and Nookachamps farmers today will understand how such calamities still happen.

65 miles upriver on horseback and then by canoe

Enter George H. Bacon, a young financier who decided to travel down from his base in Whatcom to loan money to Skagit farmers that spring and summer. He came by steamboat, the only practical form of transportation between the counties since there were no through roads, just old Indian paths that were not wide enough for a wagon. Bacon was 22 and described himself as looking to be 16 and "regarded as a freak — probably crazy — by the old-timers around the bar," but he was a good judge of character and Stevens did not pass his test. Bacon was also from Illinois and his cousin Henry designed the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. In his memoirs, Booming and panicking on Puget Sound, which his daughter published in 1970, Bacon noted that he arrived in. Skagit county just as a freshet, or spring flood, was sweeping massive logs down the river. On his first night in Mount Vernon, the Henry Bailey sternwheeler from Seattle docked next to the Washington Hotel where he was staying and out walked Amasa Everett on his peg leg, along with Lafayette Stevens. Both were seeking $3,000 loans and they were happy to meet Bacon, though Stevens cross-examined him to make sure he actually had access to such a sum. Bright and early the next morning, Stevens arranged for horses and he and Bacon set off for Stevens' upriver ranch at Sauk Prairie, a ride of about 65 miles upriver, far beyond Hamilton and on the south shore of the Skagit. They crossed the Skagit at Riverside on a cable ferry, the first that Bacon had ever seen and he describes how they rode for "interminable miles through the most wonderful fir and cedar timber I had ever seen. The only wagon road ran about thirty miles up the river and then stopped, the remainder of the journey being by trail." Soon they forded the Baker river near the present site of Concrete and stayed the first night at Everett's homestead on the east side. Bacon marveled at how Everett had cleared the whole farm, including the stumps, and put in crops, all done while hobbling on his peg. The next day they rode 40 miles through thick forest on the north shore and then swam their horses across the Skagit at the mouth of the Sauk river. Bacon describes how Stevens typically navigated the river near his ranch:

Stevens got an Indian canoe, put me in the bow, and he took the stern. We then pulled one horse into the stream, taking care that he did not climb into the canoe with us, which he was much inclined to do. I then grabbed him around the neck and held the bow of the canoe close to his head while Stevens, standing in the stern, had a long note which he alternately used as a paddle and as a prod to Mr. Horse to do a little more active swimming. So, by everybody working, we landed half-a-mile down the stream and across it, where the swift current had carried us, took out Mr. Horse and tied him, then went back for the second horse. I was very new to all this kind of thing, and I can still feel the thrill that went through this old horse's neck as he pawed the water furiously to keep his head, the canoe, and everything else above water. We stopped all night at Stevens' place on the Sauk Prairie, a natural spot of cleared land, probably an old lake bottom, in the heart of the mountains, but I was not impressed at all with the amount of cultivation that Mr. Stevens had given to his place.

Once again the promoter, Stevens may have gone overboard, figuratively, in trying to impress Bacon.

I did not quite know what to make of Stevens. In this four-day trip with him, we met many people on the trail to each of whom he introduced me as a "money man" with many flourishes and compliments to both myself and the traveler met. Invariably, after we had passed on, he would warn me against this man as being either a crook or having something wrong with him somewhere. Also he watched me so closely to see that I talked with no one while he was not present that he rather overdid it. After a few days of this, I made up my mind that there could be no country in America where they were all crooks like this — the big majority of the people must be square and honest here as elsewhere. Hence the trouble must lie with the man I was with and not with the people.

When they returned to Mount Vernon, Bacon conferred about the loans with his new friend, Dr. Horace P. Downs, the Boston-born Skagit County Auditor, who settled near the river in 1877, the year that Mount Vernon was born. "Thoroughly acquainted with farm and timber values, . . . he told me that one man was good and the other man was no good, and I made Everett a $3,000 loan which turned out to be first class in every respect." Stevens either stepped on some of the wrong toes in his business dealings or his riverboat gambler image offended the good doctor. We suspect that Stevens was cash-poor after the loss of his planting, so he probably needed the loan and its loss was a hardship for him.

|

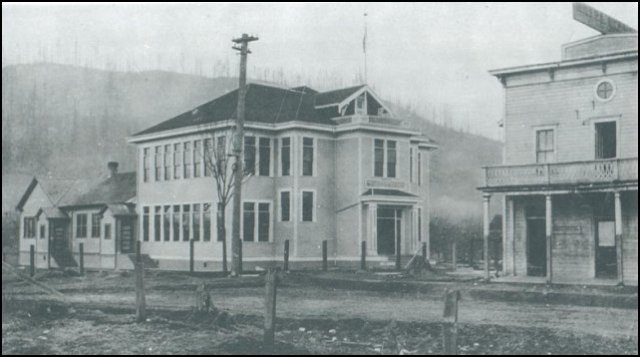

This photo is of the Lake Hotel in Clear Lake in the 1890s, with the Clear Lake school to the left. The present school is on the same spot as its forerunner, east of Hwy. 9, which runs through town. Stevens bought the hotel to the right after returning from the Klondike gold rush. Photo compliments of Deanna Ramey Ammons, Clear Lake historian.

|

Just four years later the whole country was thrown into a deep Depression that equaled the one in the 1930s. The year 1894 was a sad one for the Stevens couple as their infant daughter Esther died at age three weeks. She was named for Lafayette's widowed mother, who died two years before. By 1898, Skagit county was recovering well from the Depression because farmers and fishermen were supplying food for the miners in the Klondike gold rush in Alaska and the whole state was making money by outfitting them. Rolling the dice once more, Stevens joined the prospectors there at age 51. This time he rolled a winner, working two years with seven other men who shared $50,000 profit from a single claim, according to his biography, which may have been exaggerated. When he returned at the turn of the turn of the century, he moved his wife and family down to the town of Clear Lake, a mile south of Sedro on the south side of the Skagit. The little village of a few hundred population was growing after spending its first ten years in the shadow of the twin cities to the north. Back in 1891, a year after Jacob Bartl platted the original village of Mountain View on the site, Alexander Smith built a hotel called the Lake House. The Seattle Lake Shore & Eastern railroad from Seattle ran so close to the hotel that cinders sometimes burned holes in clothes drying on the line. Betting on the future, Stevens bought the hotel from the then-current owners, Charles Eagan and Robert Lannigan, and renamed it Stevens House. By the time the 1906 Book was published, he was well ensconced in the hotel and was once again investing in mining claims, four particular claims on nearby Table Mountain. He said the ore there assayed at $16 to the ton, principally showing as gold quartz on well-defined ledges cased with slate and greenstone. He proceeded full speed ahead at development as his wife ran the hotel.

By that time, they had four surviving children: Fred, Laura, Mabel, and Ralph. When Stevens' brother Henry died intestate in Oregon in 1931, two of Lafayette's children were listed as beneficiaries who still lived in Clear Lake, Mrs. Mabel (Stevens) Brown and Ralph Stevens, but we have not yet found records about them. Joy Lester found burial records for Florence that show she died in Clear Lake in 1911 and Joy thinks he went back to prospecting at age 64. Joy also noted that Lafayette died on July 12, 1919. We hope that a reader will be able to provide obituaries for any member of the family, more photos and details about Lafayette's mining claims, along with any other details of this adventurous man who was one of the county's first permanent upriver settlers.

Story posted on Oct. 29, 2002; last partially updated Aug. 20, 2004, and Feb. 5, 2009

Please report any broken links so we can update them

This article originally appeared in Issue 11 of our Subscribers-paid Journal online magazine

See this Journal Timeline website of local, state, national, international events for years of the pioneer period. See this Journal Timeline website of local, state, national, international events for years of the pioneer period.

Did you enjoy this story? Remember, as with all our features, this story is a draft and will evolve as we discover more information and photos. This process continues until we eventually compile a book about Northwest history. Can you help? Did you enjoy this story? Remember, as with all our features, this story is a draft and will evolve as we discover more information and photos. This process continues until we eventually compile a book about Northwest history. Can you help?

Remember; we welcome correction & criticism. Remember; we welcome correction & criticism.

Please report any broken links or files that do not open and we will send you the correct link. With more than 700 features, we depend on your report. Thank you. Please report any broken links or files that do not open and we will send you the correct link. With more than 700 features, we depend on your report. Thank you.

Read about how you can order CDs that include our photo features from the first five years of our Subscribers Edition. Perfect for gifts. Read about how you can order CDs that include our photo features from the first five years of our Subscribers Edition. Perfect for gifts.

|

You can click the donation button to contribute to the rising costs of this site. See many examples of how you can aid our project and help us continue for another ten years. You can also subscribe to our optional Subscribers-Paid Journal magazine online, which celebrated its tenth anniversary in September 2010, with exclusive stories, in-depth research and photos that are shared with our subscribers first. You can go here to read the preview edition to see examples of our in-depth research or read how and why to subscribe.

|

|

You can read the history websites about our prime sponsors

Would you like information about how to join them in advertising?

Our newest 2011 sponsor: Plumeria Bay, based in Birdsview, your source for the finest down comforters, pillows, featherbeds & duvet covers and bed linens. Order directly from their website and learn more. Our newest 2011 sponsor: Plumeria Bay, based in Birdsview, your source for the finest down comforters, pillows, featherbeds & duvet covers and bed linens. Order directly from their website and learn more.

Our newest sponsor: Gallery Cygnus, 109 Commercial St., half-block uphill from Main Street, LaConner. Open Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from 11 am to 5 p.m., featuring new monthly shows with many artists, many local. Across the street from Maple Hall, 1886 Bank Building and Marcus Anderson's 1969 historic cabin. Their new website. Our newest sponsor: Gallery Cygnus, 109 Commercial St., half-block uphill from Main Street, LaConner. Open Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from 11 am to 5 p.m., featuring new monthly shows with many artists, many local. Across the street from Maple Hall, 1886 Bank Building and Marcus Anderson's 1969 historic cabin. Their new website.

Oliver-Hammer Clothes Shop at 817 Metcalf Street in downtown Sedro-Woolley, 89 years. Oliver-Hammer Clothes Shop at 817 Metcalf Street in downtown Sedro-Woolley, 89 years.

Peace and quiet at the Alpine RV Park, just north of Marblemount on Hwy 20, day, week or month, perfect for hunting or fishing Peace and quiet at the Alpine RV Park, just north of Marblemount on Hwy 20, day, week or month, perfect for hunting or fishing

Park your RV or pitch a tent by the Skagit River, just a short drive from Winthrop or Sedro-Woolley

Joy's Sedro-Woolley Bakery-Cafe at 823 Metcalf Street in downtown Sedro-Woolley. Joy's Sedro-Woolley Bakery-Cafe at 823 Metcalf Street in downtown Sedro-Woolley.

Check out Sedro-Woolley First section for links to all stories and reasons to shop here first Check out Sedro-Woolley First section for links to all stories and reasons to shop here first

or make this your destination on your visit or vacation.

Are you looking to buy or sell a historic property, business or residence? Are you looking to buy or sell a historic property, business or residence?

We may be able to assist. Email us for details.

|

Did you find what you were seeking? We have helped many people find individual names or places, so email if you have any difficulty.

|

Tip: Put quotation marks around a specific name or item of two words or more, and then experiment with different combinations of the words without quote marks. We are currently researching some of the names most recently searched for — check the list here. Maybe you have searched for one of them?

|

Please sign our guestbook so our readers will know where you found out about us, or share something you know about the Skagit River or your memories or those of your family. Share your reactions or suggestions or comment on our Journal. Thank you for taking time out of your busy day to visit our site.

|

View My Guestbook

Sign My Guestbook

|

Email us at: skagitriverjournal@gmail.com

Mail copies/documents to Street address: Skagit River Journal, 810 Central Ave., Sedro-Woolley, WA, 98284.

|

810 Central Ave.,

810 Central Ave.,