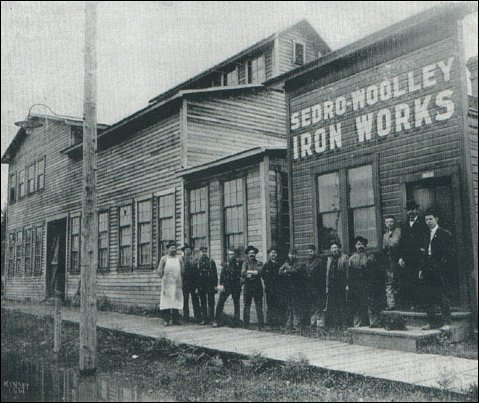

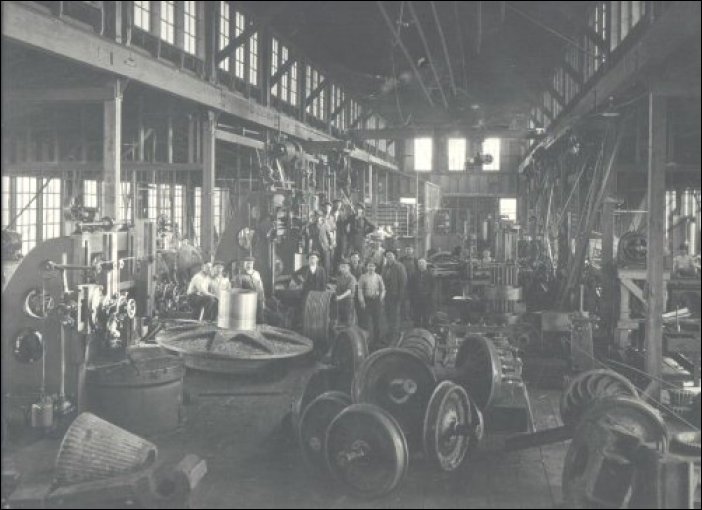

This is the original location of Sedro-Woolley Iron Works on the east side of Puget street, just south of the Seattle & Northern railroad tracks, circa 1902-05. We are looking southeast, where a manufactured home stands today. John Anderson began the business as a blacksmith in the backroom of the Fritsch Brothers Hardware store in old Woolley in 1901, as an adjunct to his larger Marysville repair shop. This photo was taken sometime in 1902 as the new plant on Puget soon became a repair shop for trains and lumber camps from here on upriver. After a fire in 1910, the plant was rebuilt west of Metcalf street near Gibson, on about the original location of P.A. Woolley's lumber camp. This photo is reproduced from the Aug. 8, 1961 Puget Sound Mail newspaper of LaConner, which is long out of print. It was loaned by Berniece Leaf.

We are able to identify some but not all men in the photo. From l. to r.: unknown boilermaker; pattern maker, unknown; Edward Clinchard, foundryman; John G. Anderson, founder, boilermaker and plant superintendent; Robert Naubert, machinist; David G. McIntyre, machinist; Benny Anderson, cupola tender and casting cleaner; Clay Gould, bookkeeper. Fred R. Faller, first president and general manager, is seated in the buggy

|

810 Central Ave.,

810 Central Ave.,