|

See this Journal Timeline website of local, state, national, international events for years of the pioneer period. See this Journal Timeline website of local, state, national, international events for years of the pioneer period.

Did you enjoy these stories and histories?

The process continues as we compile and collaborate on research about Northwest history. Can you help?

Remember; we welcome correction, criticism and additions to the record. Did you enjoy these stories and histories?

The process continues as we compile and collaborate on research about Northwest history. Can you help?

Remember; we welcome correction, criticism and additions to the record.

Please report any broken links or files that do not open and we will send you the correct link. With more than

800 features, we depend on your report. Thank you. Please report any broken links or files that do not open and we will send you the correct link. With more than

800 features, we depend on your report. Thank you. |

|

If you would like to make a donation to

contribute to the works of this website or any of the works of Skagit County Historical

Society and Museum. We thank you up front. While in your PayPal account,

consider specifying if you would like your donation restricted to a specific

area of interest: General Funds, Skagit River Journal, Skagit City School,

Facilities, Publication Committee, any upcoming Exhibit. Just add those

instructions in the box provided by PayPal.

|

|

Please sign our guestbook so our readers will know where you found out about us, or share something you know about the Skagit River or your memories or those of your family. Share your reactions or suggestions or comment on our Journal. Thank you for taking time out of your busy day to visit our site.

Currently

looking for a new guestbook!

|

View My Guestbook

Sign My Guestbook

|

Email us at: skagitriverjournal@gmail.com

Mail copies/documents to Street address: Skagit River Journal c/o Skagit County

Historical Society, PO Box 818, 501 S.4th St., La Conner, WA. 98257

|

|

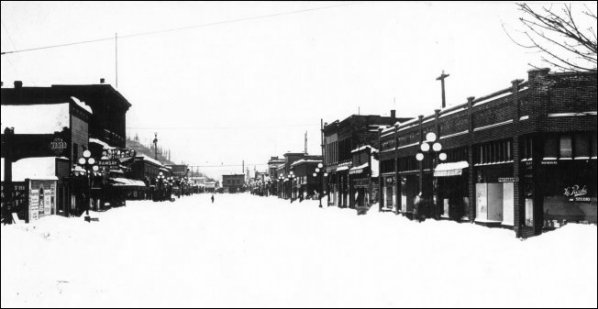

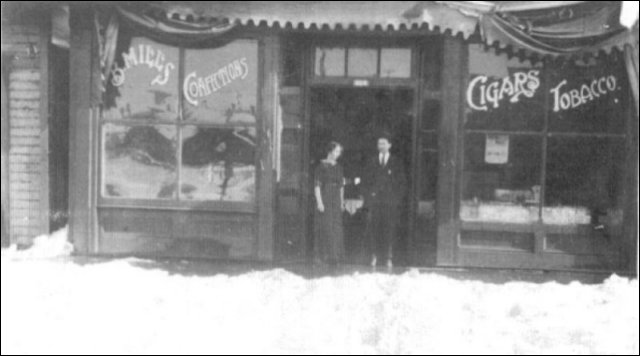

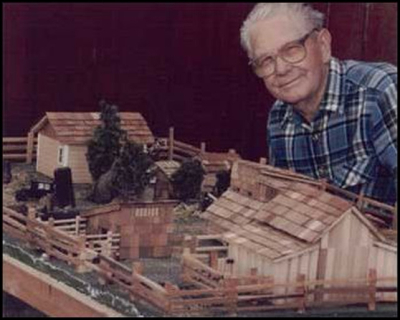

Howard Royal and his family's Birdsview Stump Ranch

Howard Royal and his family's Birdsview Stump Ranch

This page originated in our Free Pages

This page originated in our Free Pages  Covering from British Columbia to Puget Sound. Washington counties covered: Skagit, Whatcom, Island, San Juan, Snohomish.

Covering from British Columbia to Puget Sound. Washington counties covered: Skagit, Whatcom, Island, San Juan, Snohomish. An evolving history dedicated to committing random acts of historical kindness

An evolving history dedicated to committing random acts of historical kindness  Please pass on this website link to your family, relatives, friends and clients.

Please pass on this website link to your family, relatives, friends and clients.